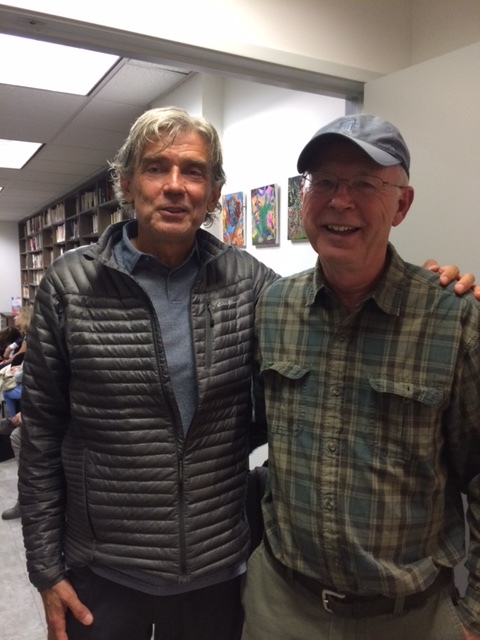

Last week I had a great conversation with Will Steger. We both grew up in Richfield, Minnesota—a suburb on the southern border of Minneapolis. Our houses were about 150 yards apart. We reminisced about the fun we had as kids building forts, digging tunnels, playing Monopoly in my basement, and rafting on Woodlake before it became a marsh. We grew up in in a stable and safe neighborhood adjacent to open fields, hills and ponds— the kind of neighborhood where people never bothered to lock their doors because it was so safe, although Garrison Keillor noted, “Of course those locks were frozen shut six months of the year.”

Us kids learned to adapt to long winters and sub-zero temperatures, but Will took it to a completely different level. When he was nineteen years old, he bought a plot of wilderness land in northern Minnesota where he built a house and learned more of his survival techniques, including how to handle a sled dog team. He said he needed the sled dogs because his house was two miles from the nearest road.

I lost touch with Will when I went off to college and medical school and settled in California, but then I started hearing about his exploits, like the first confirmed dogsled journey to the North Pole without resupply in 1986 and his unsupported dogsled 1,600 mile south to north traverse of Greenland in 1988. In 1990, he received worldwide recognition for leading six members of the International Trans-Antarctic Expedition across Antarctica the long way— from the Antarctic Peninsula in the West to the Mirny Russian Base in the East, a distance about 1000 miles more than the distance between New York and Los Angeles. During his traverse of Antarctica, Will described “the coldest conditions imaginable on the planet,” like “-120° wind chills.” To my mind, his heroic, first-ever, dogsled crossing of the frigid, stormy and hazardous Antarctic continent ranks up there with the accomplishments of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Will’s exploits have given him first-hand knowledge of the effects of global climate change. He first saw Antarctica on July 26, 1989 from the window of a Twin Otter charter plane. (Too bad he missed the thrill of crossing Drakes passage on a ship to get to Antarctica.) As he crossed the spine of mountains on the Antarctic Peninsula, he was shocked to find open waters dotted with tabular icebergs in the Weddell Sea. Normally there is dense sea ice in that area year-round, particularly along the western edge of the Antarctic Peninsula.

The first time I saw the Weddell Sea in January 1970 aboard the USCGC Glacier the sea surface was seventy-five to one hundred percent covered with pack ice—and we were not only further north than the location Will described, but also it was during the Antarctic summer. During the Antarctic winter, there is a fourfold expansion of sea ice around the continent, meaning Will should have been seeing solid icepack even before he reached the northernmost portion of the continent. A sixty-year record of temperatures now show that winter temperatures on the northwestern Antarctic Peninsula have increased by 11°F and annual average temperatures by 5°F.

Will also experienced the effects of global warming in 1995 when he led a team of five scientists and educators on an epic 1,200 mile expedition between Russia and Ellesmere Island, Canada. They traversed the polar ice pack utilizing dogsleds and canoe sleds. The feat was much harder than he had anticipated because of the unexpected absence of polar ice. The going was much slower when they had to paddle through open waters. There is now so little sea ice during the summer that cruise ships can routinely sail the Northwest Passage.

When I spoke with Will last week he indicated that one of his inspirational heroes is also one of mine, the Norwegian polar explorer, inventor, researcher and humanitarian, Fridtjof Nansen. After his legendary polar explorations, Nansen went on to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for the work he did to help resettle refugees. Like Nansen, Will expressed the need to continue to contribute to society following his major accomplishments as an explorer. He said, “Nansen’s (commitment) was refugees, mine’s education.”

Will has done an excellent job fostering education. In 1991, he co-founded the Center for Global Environmental Education. Two years later he founded the World School for Adventure Learning at the University of St. Thomas (Minnesota). In 2006, Will established the Will Steger Foundation to educate and encourage people to search for solutions to climate change. In 2014, he established the Steger Wilderness Center to demonstrate among other things practical solutions for creating a sustainable planet.

Over the course of his career, Will has received multiple awards and acknowledgments. In 1995 he received, for example, the John Oliver La Gorce Medal from the National Geographic Society. The medal is awarded for “accomplishments in geographic exploration, in the sciences and for public service to advance international understanding.” Other recipients of the award include Amelia Earhart, Robert Peary, Roald Amundsen and Jacques Cousteau. I think Will richly deserves to be held in the same high esteem as these world-famous recipients, but it bothers me that he is not nearly as famous as most of them. For example, this past week I asked several people if they had ever heard of Will Steger. They had not, but they had all heard of Jacques Cousteau. I am a scuba diver, a Francophile and a big fan of Jacques Cousteau, but up much bigger fan of Will Steger, and unlike the other luminaries I just mentioned, Will is still very much alive and engaged in tremendous work.

I encourage you all to learn more about Will Steger and his educational activities, particularly his efforts regarding climate change. He’s very well known in Minnesota, but not so much in California where I live. Each year he gives more than 100 invited presentations for private and public events, mostly through the activities of the Will Steger Foundation. I’m hoping to get him included in the lecture series I go to in Los Angeles.